When one hears the term “sell low, buy high,” it conjures up images of naïve investors being buffeted about by the twin emotions of fear and greed. The perception is that investors of this type get greedy when asset prices are high and, due to “loss aversion” (as the behavioral finance people like to call it), they tend to retreat in fear when markets recede. These investors are ruled mostly by emotion and do not view market cycles from a rational perspective.

One would think that DC plan sponsors and their advisors — who are supposedly sophisticated and not ruled by emotion — would not fall into the sell-low, buy-high trap. Nonetheless, a review of the academic literature reveals this to be the case.

Academic Research: Not a Pretty Picture

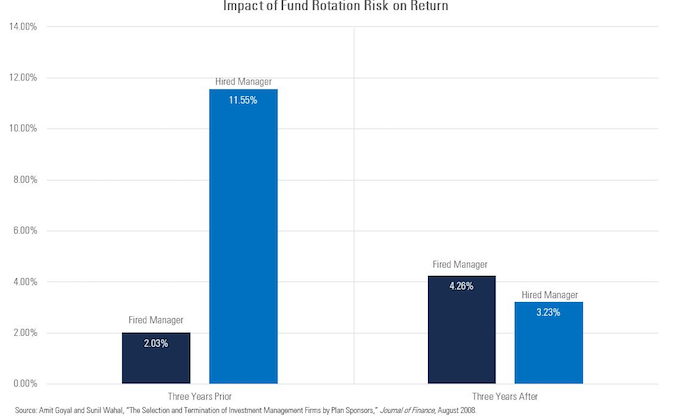

Consider the granddaddy of all the academic studies on this subject, “The Selection and Termination of Investment Management Firms by Plan Sponsors,” a paper published in 2008 by Amit Goyal and Sunil Wahal. (Goyal and Wahal) The study examined the selection and termination of investment management firms by 3,400 plan sponsors over a 10-year period. Their findings are illustrated by the following graph, which looks at the history (three years prior) and ultimate impact (three years after) of the plan sponsor’s hire/fire decisions.

The upshot is that at the time of the fire/hire decision, the terminated manager had, over the prior three years, 2.03% of excess return, while newly appointed manager had 11.55%. That sounds like a good reason to change. However, three years later the losers had beat the winners by 1.03% in excess return.

Based on their findings, the researchers concluded that “plan sponsors hire investment managers after large positive excess returns but this return chasing behavior does not deliver positive excess returns thereafter.”

Other researchers have validated Goyal and Wahal’s findings:

- “When administrators change offerings, they choose funds that did well in the past, but after the change deleted funds do better than added funds.” (Elton, Gruber, and Blake, 2007)

- “Much like individual investors who switch mutual funds at the wrong time, institutional investors do not appear to create value from their investment decisions.” (Stewart, Neumann, Knittel, and Heisler, 2009)

- “We find no evidence of improvements in return performance related to departures” (Kostovetsky and Warner, 2015)

While these studies have been consistent in their findings, “experience suggests that most investors appreciate this research but then ignore it when making decisions.” (Penfold, 2012) For DC plan advisors (especially those serving as a 3(38) fiduciary), the question is: Why is there a tendency to essentially ignore this research and continue along the path of “selling low and buying high”?

Factors Driving (Excessive) Fund Changes in DC Plans

There are forces at work in the DC market which encourage frequent hiring and firing of investment managers:

- An overemphasis on management skill in fund evaluation

- Aggressive sales efforts to grow DC advisory practices

- The emergence of low-cost, automated 3(38) services

- Regulatory and litigation concerns

What many of these academic studies essentially confirm is that managerial skill is only one component of excess return. The other important (and often ignored) elements are the random and cyclical nature of returns. Asset managers have their own distinctive investment philosophy and process. Markets are, of course, cyclical and these cycles can be influenced, set off or terminated by random events. If a manager is underperforming relative to their peers, it is often because their investment style is out of favor, while a period of outperformance is an indication that their views are in favor. Despite the often-touted ability to isolate manager skill, the reality is that this is often hard to do.

To grow their practices, plan advisors must often unseat an incumbent advisor. One strategy is to focus on poorly performing funds in an investment lineup. Although the funds may have been fine three years ago, according to a S&P Dow Jones study (Soe, 2014), the chance of a fund remaining in the top quartile three years later is less than 4%. This creates an opportunity for a new advisor to build an alternate lineup with all “top performers,” often making it appear that the incumbent advisor is not doing his or her job.

Click here to read more commentary from Jerry Bramlett.

The emergence of automated 3(38) service offerings have further exacerbated the problem of fund rotation. These investment firms often charge only a few basis points to provide a fund lineup as well as monitor and replace funds on an ongoing basis. The low cost of this service almost guarantees that the focus will be on utilizing computer models that rely heavily on quantitative measures of which past performance is the dominant metric. When advisors who for whatever reason do not wish to serve in a fiduciary capacity hire automated 3(38) platforms, it is important to understand what drives the process of hiring and firing managers and any role it may play in causing excessive fund rotation.

One of the main compliance mantras is that “DC sponsors have a duty to monitor and periodically review their investment lineup.” With the plaintiffs’ bar aggressively looking for litigation targets, plan sponsors are right to be concerned about the reasonableness and prudency of their investment lineup. Unfortunately, “monitoring and reviewing” is often primarily focused on past performance and, thus, leads to excessive fund turnover.

The Way Forward

There are essentially two primary ways out of the fund rotation trap:

- Stick with managers over the longer term

- Utilize all passive investment vehicles

Plan sponsors and their advisors choosing to utilize active managers should focus on managers for which there is every reason to believe that they will be successful – research capabilities, scale, history of adding value over their respective benchmarks, reasonable fee structures and a prudent approach to managing money. The focus should be on long-term performance (10-15 years) rather than on the shorter return periods (3-5 years). The plan’s Investment Policy Statement (IPS) should reflect this bias towards management capability, fees and long-term performance. Most importantly, the plan sponsor and the advisor should be prepared to defend their long-view perspective.

The other alternative is to pursue a passive approach to investing, which mostly leaves prior investment performance out of the evaluation equation. Instead of focusing on prior performance, the emphasis is on fees, tracking error and which asset classes are required to create efficient allocation portfolios. Just as is the case when pursuing a long-view active strategy, the IPS needs to reflect the focus on passive investing.

Conclusion

Academic studies have consistently shown the deleterious impact that excessive fund rotation has on investment returns. Overemphasis on management skill, aggressive sales tactics, automated 3(38) fiduciary platforms and heightened compliance concerns contributes to an increase in return-destroying fund turnover.

A plan advisor who is focused on enhancing participant outcomes should hit the pause button when it comes to changing out a fund, especially when the move is being driven by short-term (3-5 years) performance. As noted by the legendary investor Warren Buffett, “Frequently, the best decision is to do nothing.”

Jerry Bramlett is the Managing Partner of Redstar Advisors, a boutique consulting firm focused on digital advice solutions. This column originally appeared in the Spring issue of NAPA Net the Magazine.

REFERENCES

- Elton, Edwin J., Martin J. Gruber, and Christopher R. Blake. “Participant Reaction and the Performance of Funds Offered by 401(k) plans.” Journal of Financial Intermediation, 16.2 pp. 249 -271 (2007).

- Goyal, Amit, and Sunil Wahal. “The selection and termination of investment management firms by plan sponsors.” The Journal of Finance, 63.4 pp. 1805-1847 (2008).

- Kostovetsky, Leonard and Jerold B. Warner. “You’re fired! New evidence on portfolio manager turnover and performance.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 50.04 pp. 729-755 (2015).

- Penfold, Robin. “How much value should you expect to gain or lose by replacing your investment manager?” Journal of Asset Management, Volume 13, Issue 4, pp. 243–252 (2012).

- Soe, Aye M. “Does Past Performance Matter? The Persistence Scorecard.” S&P Dow Jones Indices, McGraw Hill Financial (2014).

- Stewart, Scott D., John J. Neumann, Christopher R. Knittel, and Jeffrey Heisler. “Absence of value: An analysis of investment allocation decisions by institutional plan sponsors.” Financial Analysts Journal, 65.6 pp. 34-51 (2009).